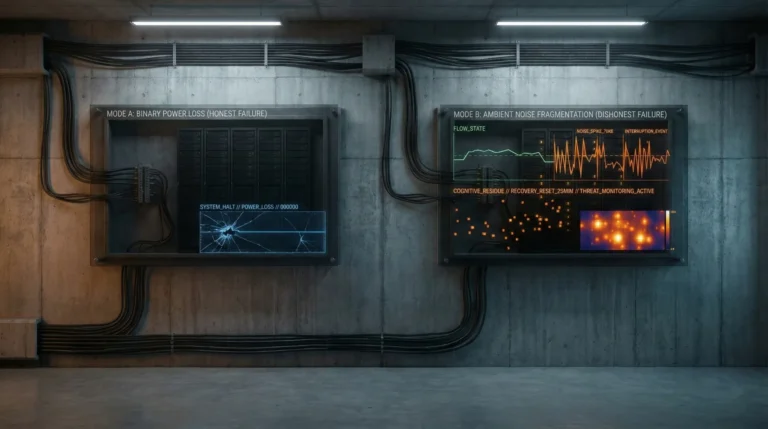

Heat doesn’t announce itself as a sudden problem. Unlike a power outage, there is no abrupt failure or clear breaking point where your equipment simply shuts down. Your laptop stays on, and the internet usually keeps working. Consequently, nothing technically “stops.”

However, that is exactly why heat is so damaging for cognitive work. It degrades thinking quietly, while you are still trying to function. Most people only notice the temperature when it becomes physically uncomfortable. Unfortunately, by then, your cognitive performance has already dropped significantly.

Working from home makes this dynamic worse, not better. While offices are designed around thermal stability, homes are not. Once you start paying attention to this variable, the pattern becomes impossible to ignore.

The First Thing Heat Takes Is Not Comfort

What heat affects first is not productivity in the abstract; specifically, it destroys decision quality. When the room warms up, I notice myself hesitating more often. For instance, I start rereading emails three times before sending them.

Furthermore, I delay starting tasks that require deep commitment. None of this feels dramatic in the moment; rather, it just feels like “one of those slow afternoons”.

The 26°C Threshold

This degradation happens earlier than expected. In my home office, I have found that anything above roughly 26°C changes how I work. This shift doesn’t happen immediately, but usually within forty to sixty minutes of crossing that threshold.

I still type, and I still respond to messages. However, the work shifts from deliberate to reactive. Ultimately, that shift is expensive for anyone paid to think.

█ FIELD NOTES: THERMAL DRIFT

- 09:00 AM (~21°C): Flow state. Complex problem solving is effortless.

- 11:30 AM (~24°C): Fan turned on. Mild physical awareness, but focus holds.

- 01:45 PM (~26.5°C): The “Sticky” Phase. I catch myself re-reading the same email three times.

- 03:20 PM (~28°C): Pseudo-productivity. I am moving windows around and organising files, but actual output is zero.

Note: The drop in cognitive quality happened at 26.5°C, a full 40 minutes before I felt “too hot” to work.

Why Homes Heat Up Faster Than You Expect

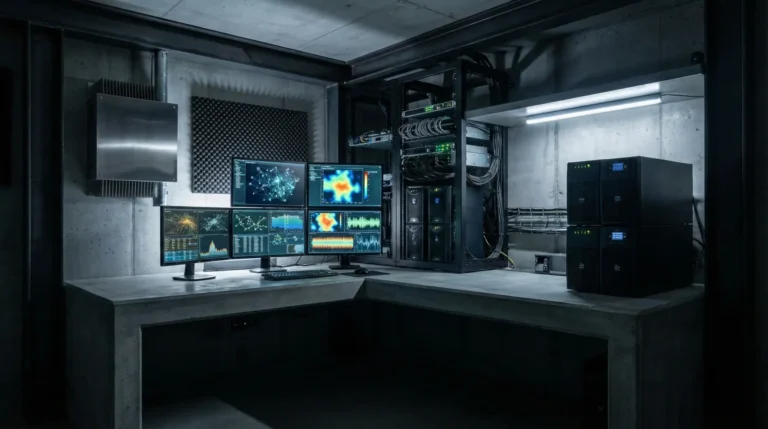

Most home workspaces are, effectively, thermal dead zones. They often suffer from a combination of factors: small square footage, closed doors, and equipment generating continuous heat.

Unlike commercial offices, residential spaces rarely have active air circulation or consistent cooling feedback loops. Consequently, once heat accumulates, it lingers. By the time you actually feel warm, the room has already been compromising your focus for a while.

This matters because cognitive performance doesn’t fail at the same temperature for everyone. However, it almost always fails earlier than physical discomfort does.

Why Fans Don’t Solve the Real Problem

Fans help with perception, not with the underlying conditions. While they move air across your skin, they do nothing to reduce the actual room temperature or CO2 levels. In fact, they often mask how bad the environment has become.

I’ve had afternoons where a fan made the room feel tolerable, yet my thinking was already degraded because the air quality remained poor. The air felt “fine,” but my output wasn’t.

This masking effect is one of the main reasons heat-related cognitive decline goes unnoticed. You don’t feel like you are struggling; you just stop doing your best work.

Heat Compounds Other Failures

Moreover, heat rarely acts alone. As temperature rises, a cascade of other issues begins:

- Laptops throttle sooner due to poor thermal management.

- Fans spin louder, increasing background noise.

- Windows get opened, letting in street noise.

Each factor on its own is manageable. Together, however, they create constant low-level friction. Nothing breaks, but everything degrades. I’ve noticed that on warmer days, interruptions feel significantly more disruptive, even if nothing else has changed. The same noise that is tolerable at 22°C becomes irritating at 28°C. That sensitivity is not psychological weakness; it is cognitive load.

The Afternoon Myth

Many people blame the time of day for their lack of focus. You often hear phrases like, “I’m just not sharp after lunch” or “I’m more productive in the morning”. Sometimes that is true due to circadian rhythms. Often, however, it is simply heat accumulation.

In my own setup, the mental drop I used to attribute to the “afternoon slump” correlates much more strongly with temperature buildup. On cooler days, that slump almost disappears. Conversely, on hot days, it arrives early and lingers. Time wasn’t the variable; environment was.

Why This Matters for Remote Work

Fundamentally, remote work assumes that your home is a neutral container for your job. In reality, it isn’t. When thermal conditions drift, work quality drifts with them. Because this drift is gradual, people tend to adapt downward instead of fixing the cause. They work slower, accept lower standards, and call it fatigue.

This is not a motivation problem; it is an infrastructure problem. Once you see that distinction, a lot of standard productivity advice starts to look incomplete. You simply cannot will your way through an environment that quietly erodes your ability to think.

The Uncomfortable Conclusion

Heat doesn’t stop you from working. Instead, it stops you from working well, all while convincing you that everything is still fine. That deception is what makes it dangerous.

If your income depends on sustained attention and good decisions, temperature is not a comfort issue. It is a strict performance constraint. Ignoring it doesn’t make it go away; it just makes the cost invisible.

You don’t need extreme solutions immediately. But you do need to notice when your environment starts negotiating against your thinking. By the time you physically feel uncomfortable, that negotiation has already been lost.